YOUR DAILY DOSE OF BOTANY – FEBRUARY 2014

Milkweed Flower Morphology and Terminology

Submitted by Scott Namestnik, snamestnik@orbisec.com

As evidenced by the number of posts about it on my blog, one my favorite genera, of showy plants at least, is the genus Asclepias (see http://handlensandbinoculars.blogspot.com/search/label/Asclepias). There are plenty of reasons to be fond of this genus, not the least of which is the important role that the lower taxa play in the life cycles of over 450 different insect species. Another reason to like this genus is that at least one species of Asclepias is known from 49 of the 50 states, so no matter where you travel around the country there is a good chance you can find a milkweed. Yet another reason is the unique floral morphology of plants in the genus Asclepias.

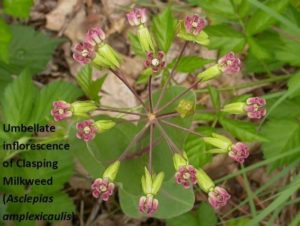

The flowers of plants in the genus Asclepias are often in clusters, with all of the flower stalks originating from a single point (an umbel). The flowers are bisexual and actinomorphic (remember what that means from the Flower Symmetry article in the October 2012 issue of The Plant Press?). Each individual flower has a five-parted calyx (sepals) and a five-parted corolla (petals). Pretty normal so far, but here’s where the flowers get interesting. Each flower often has a corona (translated: crown) arising from the middle of the corolla. The corona can look different on different species, but it often has five upright hoods that can be mistaken for petals. Each hood often contains a pointed, incurved horn, also known as a crest or beak. Surrounded by the five hoods is the gynostegium, which is a compound structure that includes the fused column of the stamens (male reproductive parts) and the heads of the styles (part of the female reproductive parts). This is where the magic happens, folks. The anthers (pollen-bearing portion of the stamens) are split into two halves, and each tw o adjacent half-anthers are connected at the corpusculum (a gland that assists in transporting pollen). Unlike plants in most other genera, in which the pollen consists of individual grains or small groups of grains, the pollen in Asclepias is grouped into waxy masses known as pollinia (pollen sacs). Crazy, I know. Here’s where it gets good. When an insect visits a milkweed flower for nectar (contained within the hoods), its legs slip into the crevices created by two adjacent half-anthers. In the process, it unknowingly picks up a pair of pollinia that it takes to the next milkweed flower that it visits. As its leg again slips into the crevice, it can distribute the pollinia if that crevice is vacant. The pollinia need to be placed precisely into the crevice or pollination will not take place. Isn’t it amazing how much is going on “behind closed doors” about which we are not even remotely aware?

o adjacent half-anthers are connected at the corpusculum (a gland that assists in transporting pollen). Unlike plants in most other genera, in which the pollen consists of individual grains or small groups of grains, the pollen in Asclepias is grouped into waxy masses known as pollinia (pollen sacs). Crazy, I know. Here’s where it gets good. When an insect visits a milkweed flower for nectar (contained within the hoods), its legs slip into the crevices created by two adjacent half-anthers. In the process, it unknowingly picks up a pair of pollinia that it takes to the next milkweed flower that it visits. As its leg again slips into the crevice, it can distribute the pollinia if that crevice is vacant. The pollinia need to be placed precisely into the crevice or pollination will not take place. Isn’t it amazing how much is going on “behind closed doors” about which we are not even remotely aware?

If you have a question about plant terminology or morphology that you would like answered in a future edition of this column, send me an email at snamestnik@orbisec.com. I may not be able to address all requests given the space allotted for this column, but I will answer those that I can.